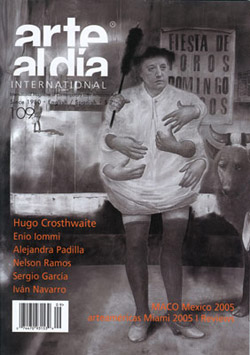

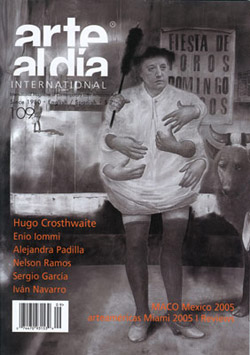

HUGO CROSTHWAITE A New Post-Modernist

Edward Lucie-Smith (London, Arte Al Dia International Magazine, Issue no.109 (June-July 2005)

Hugo Crosthwaite is a formidably gifted draftsman who belongs to a part of the Mexican and indeed the whole Latin American tradition somewhat removed from the areas occupied by either the tres grandes - the three great Mexican muralists - or the new generation of urban conceptualists now active in Mexico City. A number of Latin American artists look back to the Hispanic realism of the 17th century, imported into Latin America both through the medium of prints - mostly made in Antwerp rather than in Spain itself - and through exports from the studio of Zurbarán, which seems to have had a flourishing trade with the Spanish-speaking territories of the New World.

The residual Baroque element is extremely visible in Crosthwaite's work. It is, nevertheless, a form of the Baroque shot through with Surrealism. When André Breton arrived in Mexico and declared that certain Mexican artists, among them Frida Kahlo, were "naturally surrealist", he enunciated a truth that was profounder than he knew.

What he sensed was the clash of cultures and the profound sense of the magical that have always been typical of Latin American culture. It is not surprising that Post Modernist ideas found fertile soil in Latin America, since Latin American artists, though fascinated by European Modernism from the mid-1920s onwards, had never felt completely comfortable with aspects of the Modernist enterprise - least of all, perhaps, with its inherent elitism.

There are a number of important Latin American artists who were Post Modernist almost before the whole idea of Post Modernism was invented. They include José Luis Cuevas and Rafael Coronel in Mexico, Jacobo Borges in Venezuela and José Gamarra, originally from Uruguay, but long resident in Paris. Crosthwaite's work is essentially a new manifestation of this long-established tendency.

What these exemplars inspire them to do is to marry a feeling for what is grotesque - sometimes monstrous - with aspects of what can loosely be called classicism.

The fact that Crosthwaite's work is always in black-and-white, and often on a very large scale, concentrates one's attention both on his extremely secure grasp of form, and also on the fact that these forms are not arranged in a wholly rational way. In fact, the spectator is presented with a phantasmagoria. The artist is both horrified by the cruelty of the world and fascinated by the way in which what is grotesque becomes in a perverse way beautiful.

The exhibition at the ArtSpace/Virginia Miller Galleries in Miami provided an experience whose impact lingered for some time in the imagination. The Baroque art of the 17th century was, in its most essential form, an art of empathy. When we think about it now, we tend to think first of religious compositions, such as Rubens's Raising of the Cross or Caravaggio's Entombment and Flagellation, not of the almost equally numerous works that celebrate worldly glory.

The roots of this empathetic approach are to be found in the teachings of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Loyola's Spiritual Exercises encourage the Christian worshipper to identify closely with the sufferings of Christ and the saints. Baroque art for churches is designed to focus the senses as well as the mind - for modern spectators it endows acute physical suffering with an erotic glamour that, for contemporary taste, often seems inappropriate, but which, to the generations that immediately followed that of Loyola himself, seemed admirable and even comforting.

As an artist working in the opening years of the 21st century, Crosthwaite is operating in a world where the suffering is not visibly less, but where the certainties of Counter Reformation Christianity have almost entirely collapsed. His images are a reflection of this situation. In a brief text written recently, he says: "My art is the means to define my life. My drawings allow me to fully express my longings, my fears and my hopes. All of my joy is drafted in black and white, and my trust is affirmed by the testament of a body of work that measures my character, as well as symbolizing the transfiguration of my love and my desires."

It goes without saying that this is not an attitude that the audience of the 17th century would have understood. Seventeenth-century artists would not have understood it either. What Crosthwaite has to say is clearly the product of a post-Romantic sensibility - of something that, in artistic terms, was developed in successive stages through the personalities of, first, Delacroix and Courbet; then Van Gogh and Gauguin.

What happens in his art is not only that the Baroque is deliberately drained of colour, but that it becomes fragmented. The spectator is presented with a universe that is being, almost literally, torn joint from joint - where, compositionally as well as emotionally, nothing quite fits together. This serves, not as a moral emblem, which would be the function of a conventionally religious work, but as a testimony of the artist's state of mind at the moment when the piece was created.

Edward Lucie-Smith (London, Arte Al Dia International Magazine, Issue no.109 (June-July 2005)

Hugo Crosthwaite is a formidably gifted draftsman who belongs to a part of the Mexican and indeed the whole Latin American tradition somewhat removed from the areas occupied by either the tres grandes - the three great Mexican muralists - or the new generation of urban conceptualists now active in Mexico City. A number of Latin American artists look back to the Hispanic realism of the 17th century, imported into Latin America both through the medium of prints - mostly made in Antwerp rather than in Spain itself - and through exports from the studio of Zurbarán, which seems to have had a flourishing trade with the Spanish-speaking territories of the New World.

The residual Baroque element is extremely visible in Crosthwaite's work. It is, nevertheless, a form of the Baroque shot through with Surrealism. When André Breton arrived in Mexico and declared that certain Mexican artists, among them Frida Kahlo, were "naturally surrealist", he enunciated a truth that was profounder than he knew.

What he sensed was the clash of cultures and the profound sense of the magical that have always been typical of Latin American culture. It is not surprising that Post Modernist ideas found fertile soil in Latin America, since Latin American artists, though fascinated by European Modernism from the mid-1920s onwards, had never felt completely comfortable with aspects of the Modernist enterprise - least of all, perhaps, with its inherent elitism.

There are a number of important Latin American artists who were Post Modernist almost before the whole idea of Post Modernism was invented. They include José Luis Cuevas and Rafael Coronel in Mexico, Jacobo Borges in Venezuela and José Gamarra, originally from Uruguay, but long resident in Paris. Crosthwaite's work is essentially a new manifestation of this long-established tendency.

What these exemplars inspire them to do is to marry a feeling for what is grotesque - sometimes monstrous - with aspects of what can loosely be called classicism.

The fact that Crosthwaite's work is always in black-and-white, and often on a very large scale, concentrates one's attention both on his extremely secure grasp of form, and also on the fact that these forms are not arranged in a wholly rational way. In fact, the spectator is presented with a phantasmagoria. The artist is both horrified by the cruelty of the world and fascinated by the way in which what is grotesque becomes in a perverse way beautiful.

The exhibition at the ArtSpace/Virginia Miller Galleries in Miami provided an experience whose impact lingered for some time in the imagination. The Baroque art of the 17th century was, in its most essential form, an art of empathy. When we think about it now, we tend to think first of religious compositions, such as Rubens's Raising of the Cross or Caravaggio's Entombment and Flagellation, not of the almost equally numerous works that celebrate worldly glory.

The roots of this empathetic approach are to be found in the teachings of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Loyola's Spiritual Exercises encourage the Christian worshipper to identify closely with the sufferings of Christ and the saints. Baroque art for churches is designed to focus the senses as well as the mind - for modern spectators it endows acute physical suffering with an erotic glamour that, for contemporary taste, often seems inappropriate, but which, to the generations that immediately followed that of Loyola himself, seemed admirable and even comforting.

As an artist working in the opening years of the 21st century, Crosthwaite is operating in a world where the suffering is not visibly less, but where the certainties of Counter Reformation Christianity have almost entirely collapsed. His images are a reflection of this situation. In a brief text written recently, he says: "My art is the means to define my life. My drawings allow me to fully express my longings, my fears and my hopes. All of my joy is drafted in black and white, and my trust is affirmed by the testament of a body of work that measures my character, as well as symbolizing the transfiguration of my love and my desires."

It goes without saying that this is not an attitude that the audience of the 17th century would have understood. Seventeenth-century artists would not have understood it either. What Crosthwaite has to say is clearly the product of a post-Romantic sensibility - of something that, in artistic terms, was developed in successive stages through the personalities of, first, Delacroix and Courbet; then Van Gogh and Gauguin.

What happens in his art is not only that the Baroque is deliberately drained of colour, but that it becomes fragmented. The spectator is presented with a universe that is being, almost literally, torn joint from joint - where, compositionally as well as emotionally, nothing quite fits together. This serves, not as a moral emblem, which would be the function of a conventionally religious work, but as a testimony of the artist's state of mind at the moment when the piece was created.

Rejoneador Polidextro, detail, 2001, graphite and charcoal on wood panel