THE NEW BORDER AESTHETIC

Once Known Only as a Tourist Trap, Tijuana Has Spawned a Generation of Artists Who Have Created a Distinct Cultural Identity That Reflects the City's Hybrid Life

January 24, 2004

Josh Kun, Los Angeles Time Magazine

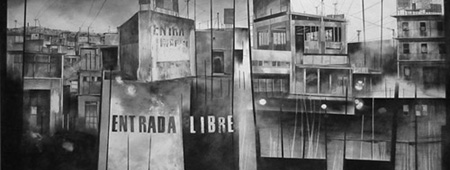

Artist Hugo Crosthwaite grew up in the heart of Tijuana. His family owns one of the many curio shops that line the main drag of Rosarito , the tourist-heavy beach town just south of Tijuana. When the 31-year-old Crosthwaite was young, he watched his parents sell home furnishings and souvenirs to tourists from the front of their home. Over time, the store grew, and so did their home out back; Crosthwaite still lives there, in a small bedroom just yards from the front of the shop. "I learned English among the curios," Crosthwaite says. I've spoken it since I was young because I had to in order to communicate with the clients who would come here. When I told my father that I wanted to be an artist, he told me, 'Be what you want, just don't be a curiosero.'" After leaving Rosarito to study graphic design in San Diego, Crosthwaite fell in love with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, and he began to dedicate himself to classical drawing. Using mostly graphite and charcoal on wood, Crosthwaite works in an intensely precise Romantic style, bringing 19th Century techniques of drawing figures and landscapes to bear on contemporary themes. His most recent large-scale piece, "Linea (Tijuana Cityscape)," eschews his usual fleshy nudes and focuses on the body of Tijuana itself, spread out into a 24-foot-long panorama of unidentifiable cement buildings. "I wanted to create a general impression of an impoverished city, where windows, doors, buildings have just been put up out of necessity," he explains from a breezy, tiled foyer of his family's home. "Just like with this very house. The home grew further back from the road simply out of our needs. That is what I want to capture in my drawings of Tijuana; that sense of impoverished construction."

While "Linea" is a tribute to Tijuana improvisation, it also is a tribute to the way the U.S.-Mexico border, known colloquially as "la linea" or "the line," has impacted the development of Tijuana as a place. As most residents will tell you, improvisation and the chaos that it brings are the city's two key aesthetic elements. People migrating north to cross the border to the U.S. end up staying in Tijuana. They build homes out of what they can (discarded refrigerator doors and tires) and where they can (on hillsides, behind stores), which led Raul Cardenas, founder of the design collective Torolab, to call the city's dominate style "emergency architecture," where "the ephemeral becomes permanent." With each wave of new arrivals, the city is reborn. And since people have not stopped coming since the '70s, Tijuana is a city that never settles into itself. It is a city in constant motion.

"The chaos is beautiful to me," Crosthwaite says. "All of its broken sidewalks, then the sidewalks that just end and suddenly there is nothing. I've lived in San Diego, in a suburb where all the houses look the same. There wasn't this visual variation, this visual beauty that chaos brings. San Diego was so planned, so organized, that I had to come back to Tijuana every weekend."

Crosthwaite had a solo show in Los Angeles ' Tropico de Nopal gallery last spring. For most of Tijuana's new crop of visual artists, exhibiting abroad is a familiar story. With only two exhibition spaces that regularly show local work (the Centro Cultural and the gallery at the Universidad Antónoma de Baja California), and virtually no local community art collectors, Tijuana artists have had to head elsewhere. Marcos Ramirez also exhibited in L.A. last spring, at the Iturralde Gallery, and Yvonne Venegas has a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego.